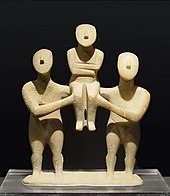

Seated Human Figure Remains One of the Most Powerful in Aegean Art

The aboriginal Cycladic civilisation flourished in the islands of the Aegean Ocean from c. 3300 to 1100 BCE.[one] Forth with the Minoan civilization and Mycenaean Hellenic republic, the Cycladic people are counted amid the three major Aegean cultures. Cycladic art therefore comprises ane of the three master branches of Aegean fine art.

The all-time known type of artwork that has survived is the marble figurine, virtually commonly a single full-length female figure with artillery folded beyond the front. The blazon is known to archaeologists as a "FAF" for "folded-arm figure(ine)". Apart from a sharply-divers nose, the faces are a polish blank, although in that location is evidence on some that they were originally painted. Considerable numbers of these are known, although unfortunately most were removed illicitly from their unrecorded archaeological context, which seems usually to be a burial.

Neolithic art [edit]

Almost all data known regarding Neolithic fine art of the Cyclades comes from the excavation site of Saliagos off Antiparos. Pottery of this flow is similar to that of Crete and the Greek mainland. Sinclair Hood writes: "A distinctive shape is a bowl on a high foot comparable with a blazon which occurs in the mainland Late Neolithic."[2]

Cycladic sculptures [edit]

Marble harp Actor (EC Two; Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe)

The best-known art of this catamenia are the marble figures usually chosen "idols" or "figurines", though neither proper name is exactly authentic: the former term suggests a religious function which is by no means agreed on past experts, and the latter does not properly employ to the largest figures, which are nigh life size. These marble figures are seen scattered effectually the Aegean, suggesting that these figures were popular among the people of Crete and mainland Hellenic republic.[three] Perhaps the most famous of these figures are musicians: one a harp-actor the other a pipage-role player.[4] Dating to approximately 2500 BCE, these musicians are sometimes considered "the earliest extant musicians from the Aegean."[5]

The majority of these figures, even so, are highly stylized representations of the female human being course, typically having a apartment, geometric quality which gives them a striking resemblance to today'south modern art. However, this may exist a modernistic misconception as there is evidence that the sculptures were originally brightly painted.[6] A majority of the figurines are female, depicted nude, and with arms folded beyond the stomach, typically with the right arm held below the left. Most writers who have considered these artifacts from an anthropological or psychological viewpoint have assumed that they are representative of a Bang-up Goddess of nature, in a tradition continuous with that of Neolithic female figures such equally the Venus of Willendorf.[7] Although some archeologists would hold,[8] this interpretation is non by and large agreed on by archeologists, among whom there is no consensus on their significance. They take been variously interpreted as idols of the gods, images of death, children'south dolls, and other things. One authority feels they were "more than than dolls and probably less than sacrosanct idols."[nine]

Suggestions that these images were idols in the strict sense—cult objects which were the focus of ritual worship—are unsupported by any archeological evidence.[10] What the archeological evidence does suggest is that these images were regularly used in funerary practice: they have all been found in graves. Yet at least some of them show clear signs of having been repaired, implying that they were objects valued by the deceased during life and were non made specifically for burial. Larger figures were likewise sometimes broken up then that but office of them was buried, a miracle for which there is no explanation. These figures apparently were buried equally with both men and women.[11] Such figures were not found in every grave.[nine] While the sculptures are most oftentimes found laid on their backs in graves, larger examples may have been ready upwardly in shrines or dwelling places.[12]

Early Cycladic art [edit]

Early Cycladic art is divided into three periods: EC I (2800–2500 BCE), EC Two (2500–2200 BCE), and EC 3 (2200–2000 BCE). The art is by no means strictly confined to one of these periods, and in some cases, even representative of more than 1 of the Cycladic islands. The art of EC I is best represented on the islands of Paros, Antiparos, and Amorgos, while EC Two is primarily seen on Syros, and EC III on Melos.[13]

Early Cycladic I (Grotta-Pelos Culture, 3300–2700 BCE) [edit]

The well-nigh important earliest groups of the Grotta–Pelos culture are Pelos, Plastiras and Louros. Pelos figurines are of schematic blazon. Both males and females, in standing position with a head and face, compose the Plastiras blazon; the rendering is naturalistic but also strangely stylized. The Louros type is seen every bit transitional, combining both schematic and naturalistic elements.[14] [15] Schematic figures are more commonly found and are very flat in profile, having elementary forms and lack a clearly defined head. Naturalistic figures are small and tend to have strange or exaggerated proportions, with long necks, angular upper bodies, and muscular legs.[xvi]

Pelos type (schematic) [edit]

The Pelos blazon figurines are different from many other Cycladic figurines as for most the gender is undetermined. The most famous of the Pelos type figurines are the "violin"-shaped figurines. On these figurines there is an unsaid elongated head, no legs and a violin-shaped body. Ane particular "violin" figurine, has breasts, artillery nether the breasts, and a pubic triangle, possibly representing a fertility goddess. Withal, since non all the figurines share these characteristics, no accurate decision tin be fabricated at this fourth dimension.

Cycladic marble figurine, Plastiras type

Plastiras type (naturalistic) [edit]

The Plastiras blazon is an early example of Cycladic figurines, named after the cemetery on Paros where they were institute.[17] The figures retain the violin-similar shape, opinion, and folded arm arrangement of their predecessors but differ in notable means. The Plastiras type is the well-nigh naturalistic type of Cycladic figurine, marked by exaggerated proportions. An ovoid head with carved facial features, including ears, sits atop an elongated neck that typically takes upward a full third of the figure'south total height.[18] The legs were carved separately for their entire length, ofttimes resulting in breakages. On female figures the pubic expanse is demarcated by an incision and the breasts are modeled. Representations of males differ in structure, simply not remarkably, possessing narrower hips and carved representations of the male person sexual organs. The figures are typically small in size, usually no larger than thirty centimeters, and are non able to stand on their ain, as the anxiety are pointed. Surviving figurines take been carved from marble, but information technology is suggested past some that they may also take been carved from wood.

Female person marble figurine from Naxos, Louros blazon (EC I–II, 2800–2700 BCE; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Female person marble figurine, Kapsala blazon (EC 2, 2700–2600 BCE; British Museum)

Louros blazon (schematic and naturalistic) [edit]

The Louros type is a category of Cycladic figurines from the Early Cycladic I phase of the Bronze Age. Combining the naturalistic and schematic approaches of earlier figure styles, the Louros type take featureless faces, a long neck, and a unproblematic torso with adulterate shoulders that tend to extend past the hips in width. The legs are shaped advisedly but are carved to separation no further than the knees or mid-calves.[eighteen] Though breasts are not indicated, figures of this type are still suggestive of the female form and tend to carry evidence of a carved pubic triangle.

Early Cycladic Ii (Keros-Syros culture, 2800–2300 BCE) [edit]

Kapsala variety [edit]

The Kapsala diverseness is a type of Cycladic effigy of the Early Cycladic II period. This variety is often thought to precede or overlap in flow with that of the canonical Spedos variety of figures. Kapsala figures differ from the approved type in that the arms are held much lower in the right-below-left folded configuration and the faces lack sculpted features other than the olfactory organ and occasionally ears.[xviii] Kapsala figures show a tendency of slenderness, peculiarly in the legs, which are much longer and lack the powerful musculature suggested in earlier forms of the sculptures. The shoulders and hips are much narrower as well, and the figures themselves are very pocket-size in size, rarely larger than thirty cm in length. Show suggests that paint is now regularly used to demarcate features such every bit the eyes and pubic triangle, rather than carving them directly. One characteristic of notation of the Kapsala variety is that some figures seem to propose pregnancy, featuring bulging stomachs with lines drawn beyond the abdomen. Similar other figures of the Early on Cycladic Two menstruation, the about defining feature of the Kapsala multifariousness is their folded-arm position.

Spedos variety [edit]

Female marble figurine, probably from Amorgos, Dokathismata diversity (EC Ii, 2800–2300 BCE; Ashmolean Museum)

The Spedos type, named after an Early Cycladic cemetery on Naxos, is the most common of Cycladic figurine types. It has the widest distribution inside the Cyclades every bit well as elsewhere, and the greatest longevity. The group equally a whole includes figurines ranging in meridian from miniature examples of 8 cm to monumental sculptures of 1.v m. With the exception of a statue of a male figure, now in the Museum of Cycladic Fine art Collection, all known works of the Spedos diverseness are female person figures.[19] Spedos figurines are typically slender elongated female forms with folded artillery. They are characterized by U-shaped heads and a deeply incised cleft between the legs.

Dokathismata diversity [edit]

The Dokathismata type is a Cycladic figure from the cease of the Early Cycladic II catamenia of the Statuary Age. With characteristics that are adult from the earlier Spedos variety, the Dokathismata figures feature broad, angular shoulders and a straight profile. Dokathismata figures are considered the well-nigh stylized of the folded-arm figures, with a long, elegant shape that displays a potent sense of geometry that is especially evident in the caput, which features an virtually triangular shape. These figures were somewhat conservatively built compared to earlier varieties, with a shallow leg cleft and connected anxiety.[18] Despite this, the figures were actually quite frail and decumbent to breakage. The return of an incised pubic triangle is also noted in the Dokathismata variety of figures.

Female person marble figurine, Chalandriani type (EC Two, 2400–2200 BCE; British Museum)

Chalandriani multifariousness [edit]

The Chalandriani variety is a type of Cycladic figure from the end of the Early Cycladic II period of the Bronze Age. Named for the cemetery on the island of Syros on which they were establish, these figures are somewhat similar in way and mannerism to the Dokathismata variety that preceded them. Chalandriani figures, notwithstanding, feature a more truncated shape in which the arms are very close to the pubic triangle and the leg crack is but indicated by a shallow groove.[18]

One feature of note with the Chalandriani variety is that the strict right-below-left configuration found in previous figures seemed to have relaxed, as some sculptures have reversed arms or even abandonment of the folded position for 1 or both arms. The reclining position of previous figures is likewise challenged, every bit the feet are not e'er inclined and the legs are somewhat rigid. The shoulders were expanded fifty-fifty further from the Dokathismata multifariousness and were quite susceptible to harm as the upper artillery and shoulders are also the thinnest point of the sculpture. The caput is triangular or shield-shaped with few facial features other than a prominent nose, connected to the body by a pyramidal-shaped neck. Similar figures of the Dokathismata multifariousness, some Chalandriani figures appear to be presented as pregnant. The defining characteristic of these figures is their bold and exaggerated indication of the shoulders and upper artillery.

Early Minoan examples [edit]

Koumasa variety [edit]

Koumasa figurines, from the Early Minoan II cemetery at Koumasa on Crete, are very pocket-sized and flat. The folded-arm figures typically have brusque legs and wide shoulders,[twenty] and were prone to breakage given their delicate build.[21]

Cycladic "frying pan", terracotta with stamped and cutting spirals ornamentation (EC I–II, c. 2700 BCE, Kampos stage)

Pottery [edit]

The local clay proved hard for artists to work with, and the pottery, plates, and vases of this period are seldom above mediocre.[13] Of some importance are the so-called 'frying pans', which emerged on the island of Syros during the EC II phase. These are circular busy disks, which were not used for cooking, but possibly as fertility charms or mirrors.[22] Some zoological figurines and pieces depicting ships have also been establish.

Besides these, other forms of functional pottery have been found. All pottery of early Cycladic culture was made by hand, and typically was a black or red color, though pottery of a pale buff has as well been found. The most common shapes are cylindrical boxes, known as pyxides, and collared jars.[16] They are crude in construction, with thick walls and crumbling imperfections, simply sometimes feature naturalistic designs reminiscent of the ocean-based culture of the Aegean islands. There are too figurines of animals.

Gallery [edit]

-

Female torso in darker stone with a pigsty in the throat and dírkama thighs, Plastiras blazon (EC I, 2800–2700 BCE; Museum of Prehistoric Thera) -

Early on terracotta figurines from Santorini (c. 2100 BCE; Museum of Cycladic Culture)

-

Gold figure of an ibex from Santorini, late Cycladic (17th century BCE)

See as well [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

- Akrotiri (prehistoric city) for additional artistic, decorative, and functional items excavated from an ancient Cycladic site.

- Keros-Syros culture

- Grotta–Pelos civilization

Notes [edit]

- ^ Adams, Laurie (1999). Art Beyond Fourth dimension (fourth ed.). Mc-Graw Hill. p. 112.

- ^ Hood 28

- ^ Doumas, p. 81

- ^ Higgins, p. 61

- ^ Higgins, p. threescore

- ^ Getty Museum, past exhibition "Prehistoric Arts of the Eastern Mediterranean"

- ^ Marija Gimbutas, The Linguistic communication of the Goddess, HarperCollins 1991 p. 203; Erich Neumann, The Swell Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype tr. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press, 2nd ed. 1963, p. 113.)

- ^ J. Thimme, Die Religioese Bedeutung der Kykladenidole, Antike Kunst 8 (9165), pp. 72–86

- ^ a b Emily Vermeule, Greece in the Statuary Age, University of Chicago Printing 1974, p. 52.

- ^ L. Marangou, Cycladic Culture: Naxos in the 3rd Millennium BC Athens 1990 pp. 101, 141 [sic]

- ^ Marangou p. 101

- ^ Bothmer, Bernard (1974). Brief Guide to the Section of Egyptian and Classical Art. Brooklyn, NY: The Brooklyn Museum. p. 20.

- ^ a b Higgins 53

- ^ "Cycladic Civilisation". Lake Wood Higher. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Vianello, Andrea. "Cycladic figurines in funerary rituals". BrozeAge.org. Archived from the original on 21 Apr 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ a b Fitton, J. Lesley (1989). Cycladic Art. London: British Museum Press. p. 22. ISBN978-0714112930.

- ^ Getz-Preziosi, Pat (1987). Early Cycladic Art in North American Collections. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e Getz-Gentle, Pat (2001). Personal Styles in Early Cycladic Sculpture . Seattle and London: Academy of Washington Printing.

- ^ Spedos diverseness figurine Archived 2014-08-xix at the Wayback Automobile The Museum of Cycladic Art

- ^ "Cycladic fine art: figure in the Koumasa variety". Bradshaw Foundation.

- ^ Getz-Preziosi, Pat (1982). "Risk and Repair in Early on Cycladic Sculpture" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum Periodical. 18: 24.

- ^ Higgins 54

- ^ "Harp Histrion, Early on Cycladic flow (Bronze historic period)". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

References [edit]

- Doumas, Christos (1969). Early on Cycladic Fine art. Frederick A. Praeger, Inc.

- Higgins, Reynold (1967). Minoan and Mycenaean Art. Thames and Hudson.

- Hood, Sinclair (1978). The Arts in Prehistoric Greece. Penguin Books.

External links [edit]

- The Cycladic Sculptures

- Greek fine art of the Aegean Islands, Issued in connection with an exhibition held November ane, 1979 – February x, 1980, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, sponsored by the Government of the Republic of Hellenic republic, complemented by a loan from the Musée du Louvre

duryeacamuctued96.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cycladic_art